what did the union government tax in order to help meet the cost of the war?

Front of Confederate notes (dorsum was unprinted)

Amalgamated war finance involved the diverse means, fiscal and monetary, through which the Confederate States of America financed its war effort during the American Civil War of 1861-1865. As the war lasted for virtually the entire existence of the Confederacy, war machine considerations dominated national finance.

Early in the war the Confederacy relied more often than not on tariffs on imports and on taxes on exports to raise revenues. Yet, with the imposition of a voluntary cocky-embargo in 1861 (intended to "starve" Europe of cotton and strength diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy), as well every bit the occludent of Southern ports, declared in Apr 1861 and enforced by the Union Navy, the acquirement from taxes on international trade declined. Too, the financing obtained through early on voluntary donations of coins and bullion from individual individuals in back up of the Confederate cause, which early on proved quite substantial, stale up past the end of 1861. As a result, the Amalgamated authorities had to resort to other ways of financing its military operations. A "war-revenue enhancement" was enacted simply proved difficult to collect. Likewise, the appropriation of Union holding in the Southward and the forced repudiation of debts owned by Southerners to Northerners failed to raise substantial acquirement. The subsequent issuance of government debt and substantial printing of the Confederate dollars contributed to high inflation, which plagued the Confederacy until the stop of the war. Military setbacks in the field also played a office past causing loss of confidence and by fueling inflationary expectations.[1]

At the showtime of the war, the Confederate dollar cost 90¢ worth of aureate (Matrimony) dollars. By the state of war's cease, its cost had dropped to .017¢.[2] Overall, prices in the Southward increased past more than than 9000% during the state of war.[3] The Secretary of the Treasury of the Confederate States, Christopher Memminger (in office 1861-1864), was keenly aware of the economical problems posed by inflation and loss of conviction. Still, political considerations limited internal tax ability, and as long as the voluntary embargo and the Union blockade remained in place, it was impossible to find adequate alternative sources of finance.[1]

Tax finance [edit]

The South financed a much lower proportion of its expenditures through direct taxes than the N. The share of direct taxes in full revenue for the North was about xx%, while for the South the same share was but about 8%. Much of the reason that tax acquirement did not play as large a role for the Confederacy was the private states' opposition to a strong central government and the belief in states' rights, which precluded giving as well much taxing power to the government in Richmond. Historically the states had invested footling money in infrastructure or public goods. Some other factor for non extending the tax system more than broadly was the belief, which was present in both the North and the Due south, that the war would be of limited duration and so there was no compelling reason to increase the tax burden.[1] [4]

However, the realities of the prolonged war, the necessity of paying interest on existing debt, and the drib in revenues from other sources, forced both the key Confederate government and the individual states to concur by the middle of 1861 to an imposition of a "War Taxation." Passed on Baronial 15, 1861, the law covered belongings of more than $500 (Confederate) in value and several luxury items. The tax was also levied on buying of slaves. However, the taxation proved very difficult to collect. In 1862, but v% of full acquirement came from directly taxes, and it was not until 1864 that the amount reached the still-depression level of 10%.[1]

Taking business relationship of difficulty of collection, the Confederate Congress passed a tax in kind in April 1863, which was prepare at ane 10th of all agricultural product by state. The tax was directly tied to the provisioning of the Confederate Army, and although information technology also ran into some collection problems, information technology was by and large successful. After its implementation, it accounted for about half of total acquirement if it was converted into currency equivalent.[1]

Budgetary finance and inflation [edit]

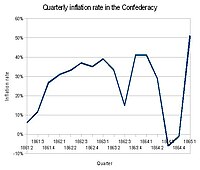

Monthly toll index in the Confederacy during the state of war rose from 100 in January 1861 to over 9200 in April 1865. In addition to being fueled past dramatic increases in amount of coin in circulation, prices also increased in response to negative news from the battleground.

The financing of state of war expenditures by the ways of currency issues (printing money) was past far the major avenue resorted to by the Confederate government. Between 1862 and 1865, more than sixty% of total revenue was created in this way.[iv] While the N doubled its money supply during the state of war, the money supply in the South increased xx times over.[5]

The all-encompassing reliance on the money-printing press to finance the war contributed significantly to the high inflation the Due south experienced over the class of the war, although fiscal matters and negative war news as well played a function. Estimates of the extent of inflation vary by source, method used, estimation technique, and definition of the aggregate price level. According to a archetype study past Eugene Lerner in 1956, a standard toll alphabetize of bolt rose from 100 at the starting time of the war to more than 9200 by the war's de facto end in April 1865.[5] By Oct 1864, the price index was at 2800, which implies that a very large portion of the rise in prices occurred in the final six months of the war.[iii] This drop in the demand for coin, the corresponding increase in "velocity of coin" (see adjacent paragraph) and the resulting rapid increment in the price level has been attributed to the loss of conviction in Southern military victory or the success of the South's bid for independence.[three]

Quarterly inflation in the Confederacy during the war. Inflation is calculated equally log growth rate of Lerner's price index.[ane]

Lerner used the quantity theory of money to decompose the inflation in the Confederacy during the war into that resulting from increases in coin supply, changes in the velocity of coin, and the change in real output of the Southern economic system. Co-ordinate to the equation of substitution:

where M is the coin supply, 5 is the velocity of money (related to people's demand for money), P is the price level and Y is real output. If it is assumed that real incomes remained constant in the S during the war (Lerner actually concluded that they fell by about 40%[3]) then the equation implies that for the toll level to increase 92 times in the presence of a twenty times increase in money supply, the velocity of coin must accept increased iv.6 times over (92/20=4.6), reflecting a very significant drib in the need for money.[5] [vi]

The problems of money-acquired inflation were exacerbated by the influx of counterfeit bills from the North. These were plentiful because Southern "Greybacks" were fairly crude and like shooting fish in a barrel to copy, as the Confederacy lacked modern printing equipment. One of the almost prolific and about famous of the Northern counterfeiters was Samuel C. Upham from Philadelphia. By one calculation Upham'due south notes fabricated upwardly between 1 and 2.5 per centum of all of the Amalgamated coin supply between June 1862 and August 1863.[vii] Jefferson Davis placed a $ten,000 compensation on Upham, though the "Yankee Scoundrel", as he was known in the South, evaded capture by Southern agents.[three] Counterfeiting was a trouble for the North as well, and the U.s.a. Secret Service was formed to deal with this problem.

The Confederate "Greyback". Note the stamp which indicates interest paid. Interest-paying money was i of the unique aspects of Amalgamated public finance.

On April i, 1864, the Currency Reform Deed of 1864 went into effect. This decreased the Southern money supply by ane-third. However, because of Union command of the Mississippi River, until Jan 1865 the law was effective only east of the Mississippi.[3]

A fairly peculiar economic phenomenon occurred during the war in that the Amalgamated government issued both regular coin notes and interest-bearing coin.[iii] The U.s.a. as well issued Interest Bearing Notes during the state of war that were legal tender for most financial transactions. The circulation of the interest-bearing money and the convertibility of one kind of money into the other was enforced past fiat and Southern banks were threatened with a render to the gold standard if they did not cooperate.[3] Because of the amount of Southern debt held by foreigners, to ease currency convertibility, in 1863 the Confederate Congress decided to adopt the gold standard. Simply convertibility was not implemented until 1879 (the 1863 law was never implemented, equally it was superseded by the Coinage Act of 1873[2] and the end of the Confederacy).

Debt finance [edit]

Quarterly growth rate of the Amalgamated primary deficit in real terms. The negative values after tertiary quarter 1862 reflect mostly the inability to find willing purchasers for Confederate debt, every bit the military situation of the S deteriorated.[1]

Issued loans deemed for roughly 21% of the finance of Confederate state of war expenditure.[iv] Initially the Southward was more successful in selling debt than the North,[2] partially because New Orleans was a major fiscal center. Its financiers bought up ii-fifths of a 15 million dollar loan in early 1861.[8]

The two main types of loans issued by the South during the war were "Cotton Bonds", denominated in pounds sterling and sold in London, and high take a chance unbacked loans sold in the Netherlands.[three] The Cotton Bonds were convertible direct into bales of cotton, with a caveat, included as a means of political force per unit area on European countries to recognize the Confederacy, that any such shipments needed to be picked upwardly past the bondholder in 1 of the blockaded Southern ports (more often than not New Orleans).[3]

Cotton Bonds initially were very popular and in high demand amid the British; William Ewart Gladstone, who at the time was the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was supposedly ane of the buyers--his family fortune came from slavery in the West Indies. The Confederate authorities managed to honor the Cotton wool Bonds throughout the state of war, and in fact their toll rose steeply until the fall of Atlanta to Sherman. This rise reflected both the increase in the underlying cotton fiber prices and perhaps the possibility that George B. McClellan might get elected as US President on a peace platform. In contrast, the price of the Dutch-issued high risk loans fell throughout the war, and the South selectively defaulted on servicing these obligations.[3]

In France vigorous fund raising yielded £3 million (about $14.5 in Us dollars) from the 1862 bond sale to the Erlanger banking concern in Paris. It was not repeated.[9]

The principal Confederacy failure was its banking on European fiscal back up and armed forces intervention but it proved a fallacy that "Cotton wool is King". Britain needed Northern grain more urgently than Southern cotton wool, for it had large stocks of cotton when the war began.[x]

Acquirement from international trade [edit]

USS Monitor in action with CSS Virginia, March 9, 1862. The Union occludent seriously hampered the Confederacy's ability to raise acquirement through import tariffs.

In the beginning of the war, the majority of finance for the Southern government came via duties on international trade. The import tariff, enacted in May 1861, was set at 12.v% and it roughly matched in coverage the previously existing Federal tariff, the Tariff of 1857.[11] Between February 17 and May 1 of 1861, 65% of all authorities revenue was raised from the import tariff. However, revenue from the tariffs all only disappeared after the Union imposed its blockade of Southern coasts. By November 1861 the proportion of government acquirement coming from custom duties had dropped to one-half of one pct.[ane] Secretarial assistant of Treasure Memminger had expected that the tariff would bring in well-nigh 25 1000000 dollars in revenue in the showtime year alone. But the total acquirement raised in this way during the entire state of war was simply virtually $iii.4 million.[1] [11]

A similar source of funds was to be the tax on exports of cotton. Nevertheless, in addition to the difficulties associated with the blockade, the self-imposed embargo on cotton meant that for all practical purposes the taxation was completely ineffective equally a fund raiser.[1] Initial optimistic estimates of revenue to exist nerveless through this tax ran as loftier as 20 million dollars, merely in the end only $30,000 was nerveless.[11]

Other sources of acquirement [edit]

Confederate one-half dollar money

The Confederate government as well tried to raise revenue through unorthodox means. In the starting time one-half of 1861, when the back up for secession and the armed services endeavor was running stiff, the donation of coins and gilt to the authorities accounted for near 35% of all sources of authorities funds. This source, however, dried upward over time as individuals and institutions in the South both ran down their personal holdings of bullion and became less willing to brand donations equally war-weariness gear up in. As a consequence, by the summer of 1862, the share of regime acquirement coming from these donations fell to less than 1%. Over the course of the unabridged war, this source of revenue contributed only 0.2% of full wartime expenditure.[1]

Some other potential source of finance could be found in the property and concrete capital owned past Northerners in the S, and the debts owed by individuals in a parallel style. The Sequestration Act of 1861 provided for confiscation of all Union "lands, tenements, goods and chattels, right and credits" and the transfer of debt obligation on the part of Confederate citizens from Northern creditors directly to the Confederate authorities. Still, many Southerners proved unwilling to transfer their debt obligations. Furthermore, what exactly constituted "Northern property" proved difficult to define in do. As a result, the share of this source of revenue in government funding never exceeded 0.34% and ultimately contributed merely 0.25% to the overall financial war effort.[i]

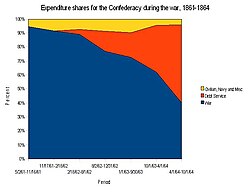

Expenditures [edit]

Shares of expenditures by category, 1861 to 1864.

While, unsurprisingly, armed forces spending constituted the largest part of the national government's budget over the form of the war, over time the payment of interest and main on acquired debt grew equally a share of the Confederate government'southward expenditure. While initially, in early 1861, war expenditure was 95% of the upkeep, by October 1864 that share savage to xl%, with the bulk of the rest (56% overall) being accounted for past debt service. Civilian expenditures and spending on the Navy (recorded separately from general war expenditures in Confederate records) never exceeded 10% of the budget.[i]

See likewise [edit]

- Economic history of the U.s.a. Civil State of war

- Economy of the Confederate States of America

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j thousand l m Burdekin and Langdana, pp. 352–362

- ^ a b c Neal, p. xxiii

- ^ a b c d eastward f chiliad h i j k Weidenmier

- ^ a b c Godfrey, p. 14

- ^ a b c Tregarthen, Rittenberg, p. 240

- ^ Lerner, Journal of Political Economic system

- ^ Weidenmier, Business and Economic History

- ^ Weigley, p. 69

- ^ Judith Fenner Gentry, "A Confederate Success in Europe: The Erlanger Loan." Journal of Southern History 36#ii (1970), pp. 157–88, online.

- ^ Eli Ginzberg, "The economics of British neutrality during the American Civil War." Agricultural History 10.4 (1936): 147-156.

- ^ a b c Todd, p. 123

References [edit]

- Richard Burdekin and Farrokh Langdana, "War Finance in the Southern Confederacy, 1861-1865", Explorations in Economic History, Vol xxx, No 3, July 1993.

- John Munro Godfrey, "Monetary expansion in the Confederacy", Dissertations in American economical history, Ayer Publishing, 1978.

- Niall Ferguson, The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the Earth, Penguin Group, 2008.

- Judith Fenner Gentry, "A Amalgamated Success in Europe: The Erlanger Loan." Journal of Southern History 36#ii (1970), pp. 157–88, online.

- Eli Ginzberg, "The economics of British neutrality during the American Civil War." Agricultural History ten.4 (1936): 147-156.

- Eugene Lerner, "Money, Prices and Wages in the Confederacy, 1861-1865", Periodical of Political Economic system, 63, 1955.

- Larry Neal, War Finance, Volume 1, Volume 12 of The International Library of Macroeconomic and Financial History, Edward Elgar Publishing, 1994.

- Richard Cecil Todd, "Confederate Finance", University of Georgia Press, 2009.

- Timothy D. Tregarthen, Libby Rittenberg, Macroeconomics, Macmillan, 1999, p. 240.

- Marc Weidenmier, "Coin and Finance in the Confederate States of America", EH.Net Encyclopedia.

- Marc Weidenmier, "Artificial Money Matters: Sam Upham and His Confederate Counterfeiting Business concern" Business and Economic History 28 no. 2 (1999b): 313-324.

- Russell Frank Weigley, A Peachy Ceremonious War: A Military and Political History, 1861-1865, Indiana University Press, 2000.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confederate_war_finance

Post a Comment for "what did the union government tax in order to help meet the cost of the war?"